Is that kind of support something for hams to be proud of? Do these hams have an effective plan that provides both unit-to-unit communications during internal phone failures and hospital-to-outside-world communications during disasters?

Is that kind of support something for hams to be proud of? Do these hams have an effective plan that provides both unit-to-unit communications during internal phone failures and hospital-to-outside-world communications during disasters?

Your First Steps

Based on 38 years of experience, here is our take on the priorities and issues facing leaders of Amateur Radio emergency groups wanting to provide emergency communications for their local hospitals.

When a busy hospital loses its telephone service for any reason, it's a potential disaster for the staff and the patients. Admitting orders, requests for supplies, medicine and blood, as well as calls to the Code Blue team are dependent on the telephone and paging systems. Amateur Radio operators can meet all these communications needs while normal systems are being restored, but there are right and wrong ways to do it.

Pop Quiz

Let's say you are the leader of a local or regional Amateur Radio emergency communications organization. You have read about HDSCS and you realize that hospitals in your area will need communications help in the next telephone equipment failure or widespread disaster, and that either could occur at any time. What should your first priority be in providing effective support to them?

A. Install an Amateur Radio station in each hospital

B. Hold a class to get the hospital employees licensed

C. Set up alerting plans for hospitals to get rapid help from your group

The correct answer is "C" but far too many hams around the country don't realize it. When we meet them at conventions and other gatherings and we ask if their ARES/RACES groups support the local hospitals, they proudly tell us "yes," simply because they have installed ham stations at all the hospitals. We ask them if a hospital's phones were to fail at that minute, would that hospital know how to contact the ham group? Would enough members of the ham group be prepared to respond immediately for an indeterminate period of time? Far too often, we get a blank stare in return.

Orange County hospitals would not have been helped through communications emergencies over 120 times since 1980 if it were not for our personal preparedness and well thought out alerting system. More about that later, but first let's dig deeper into why answers A and B are wrong.

Equipment Is Not a Plan

"Our town just bought a new fire engine! We keep it in a locked barn ten miles outside the city. Now we'll never have to worry about a building burning down."

If someone told you that, you would think it's absurd. What good is a fire engine that's far away from all the buildings that need protecting?

What if you inquired further about the town's fire preparation and you were told that only one person had the key to the barn, nobody knew how to drive the fire engine, and the fire department had a disconnected number. Even more absurd, you say? Yes, but that's a good analogy for the way some ham groups around the country have been "supporting" their local hospitals.

Some hospital managers from outside our area have told us that when they talk to local ham groups about emergency communications, the first thing the hams want is for the hospital to spend thousands of dollars to install a complete HF/VHF ham station. The hams then say that they don't have enough members in their group, so the hospital should get a bunch of its employees licensed. The hams' leader then says that if they ever need more help, they can just phone him, or get on the air and call.

Is that kind of support something for hams to be proud of? Do these hams have an effective plan that provides both unit-to-unit communications during internal phone failures and hospital-to-outside-world communications during disasters?

Is that kind of support something for hams to be proud of? Do these hams have an effective plan that provides both unit-to-unit communications during internal phone failures and hospital-to-outside-world communications during disasters?

Just an Antenna

In the HDSCS model, supported hospitals install a VHF/UHF antenna with coax going to the inside of the Hospital Command Center. The ham operators are all prepared to bring in their own transceivers to connect to the antenna for hospital-to-hospital and hospital-to-EOC communications. Their self-contained setups can also be stationed within the hospital for unit-to-unit communications. They prepare to deploy temporary antennas if the hospitals antenna is damaged or unavailable.

In our experience, only the antennas are needed. Complete permanently installed stations are disadvantageous for several reasons:

Installed stations merely create a false sense of adequate preparedness. Over the years, with just a few of our hospitals having pre-installed stations, we have seen each of these problems and have found that in almost every instance a well-prepared member can get into a hospital and get on the air faster and more effectively with his or her own gear than with any pre-installed station.

What about equipment for the HF (long distance) ham bands? Why not use packet radio, Winlink, ATV and other special modes? Those are frequently asked questions and the answers are here.

We hope that hams around the USA will take our advice and experience and will base their hospital support on portable and flexible community responders instead of depending on pre-installed equipment and licensed employees. It's OK if you think our experience means nothing and that you simply must have complete stations installed in your local hospitals. However, it's not OK to make your Amateur Radio response contingent on the hospitals installing this equipment for you. It's not OK to wait for the hospital equipment to be installed before the ham operators do their personal preparedness. And it's absolutely not OK to get the equipment installed and think that the job is done. You still need a cadre of well-prepared community hams and a robust alerting plan. If you stop before taking those steps, you are doing a major disservice to the hospitals and to Amateur Radio.

Community Hams are Dedicated Communicators

Getting hospital employees to obtain ham licenses may be good for Amateur Radio statistics, but it's not the answer to hospital emergency communications. No employee is at the hospital 24/7/365. And when employees are there, they have other tasks to perform. When disaster strikes, they will be too busy to pay attention to the Amateur Radio network and get information that is important to their facility.

In our experience, for every area-wide communications emergency such as an earthquake, flood or firestorm, there have been four single-hospital incidents such as telephone switching equipment failures, cables cut by backhoes, and so forth. These isolated incidents are just as threatening to patient well-being as the widespread emergencies. On average, HDSCS has deployed a total of eleven hams for first response and relief in each of these single-hospital phone failure callouts, sometimes lots more. Having a few hospital employees with ham tickets would be far from enough, and when those employees are not at the facility in the wee hours, how will the hospital get ham help?

Only about five per cent of HDSCS members have been employed by hospitals. These hospital employees with ham licenses provide a valuable liaison with their facilities. They help educate our members on medical matters and communications needs. They know that they cannot fill the emergency communications needs of their facilities by themselves and that they need the other 95 per cent of the membership to be ready to help them when communications fail. They also know that HDSCS served over thirty hospitals in the county. By joining HDSCS, they agreed to serve at any of the other 35 hospitals when needed, in addition to their own.

Direct Call-up Saves Vital Minutes

On a daily basis, hospital communications are time-critical and life-critical, so when phones fail, hams must be summoned to the hospital as quickly as possible. There are four crucial components to a successful activation procedure:

A plan for the hospitals to contact the Amateur Radio emergency group directly is vital. Any "middlemen" waste precious time. We have learned that in some other places, RACES and ARES teams insist that hospitals first make contact wityh the fire department or law enforcement agency that sponsors the RACES group. In turn, these public safety officials are supposed to initiate a callout of the hams. This two-step process creates inevitable and unacceptable delays, even if the public safety agency is prompt in responding to the hospital's request.

A single-hospital phone outage is unlikely to become an officially-declared disaster, even though it can be disastrous for individual patients in critical condition within that hospital. How will government officials prioritize the phone failure, compared to a major fire or car chase that may be ongoing at the same time? In a mass-casualty situation, police and fire agencies may not be aware of any resulting hospital phone overload, and a callout for hams to go to the hospitals will not be near the top of their action lists.

Operating within the ARRL Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES) structure makes possible a one-step process for hospitals to contact HDSCS directly. We know that this saves valuable time. In at least two phone failures, the first HDSCS responders were on site providing communications, with more on the way, when the Orange County Communications Center called to alert us about the same outage. It was good to have the backup of the Communications Center's call, but the hospital's ability to directly alert us earlier had saved an hour of priceless time.

An alerting plan is not adequate without redundancy in both the hams to be called and the methods to call them. No ham operator is available every hour of every day, yet we have had hospital personnel from outside our area tell us, "The leader of the Podunk ham club gave me his card and said if I ever had a communications problem to just call him."

Do you really think that's a plan? What if the ham's phone line is busy or the hospital gets his phone machine? Worse yet, what if the hospital calls two years later and finds out that the ham contact is deceased? (We have heard that this actually happened in another state!)

In the HDSCS model, every supported hospital is given its own Call-up List of at least four persons for daytime/weekdays and four for evening/weekends. Depending on availability, the same hams might be on both day and evening lists. In every case, the persons on the Call-up List are normally available by phone at that time of day. They are not necessarily first responders themselves, but they are well versed on the activation procedures of HDSCS and can initiate the callout.

After a member on the Call-up List receives an emergency call from a hospital and obtains information on the emergency, it is up to him or her to immediately initiate an appropriate activation of the system. Hospital staff need not take the time to make additional calls for us after the first successful one. Upon being called, the member first contacts one or more of the Coordinators. He or she then responds to the hospital, calls other members to do so or establishes Net Control, as directed by the Coordinator.

Names on the Call-up Lists should be a mix of HDSCS Coordinators and experienced members. All should be knowledgeable in the information that must be obtained from the calling hospital and should be very familiar with how the Amateur Radio team functions. Because Orange County is a large area, the Call-up Lists reflect the geographic distribution of the members. Wherever possible, persons on each hospital's list should be within a few minutes' drive of the facility.

You are probably wondering how hams can be contacted by a hospital if its phones can't be used. Depending on the nature of the outage, there are several effective alternatives. When switchboard equipment fails and underground lines are intact, hams have been contacted from pay phones. Many hospitals have a few emergency phones that are separate from the main system, or a special emergency system that takes over the trunks when the normal switchboard goes down. Though such systems have only a very limited number of lines, they are adequate to activate the Amateur Radio team. Fax and modem lines separate from the main phone system are another possibility.

When underground cables are severed, affecting all lines to and from the hospital, cell phones have been used by hospital staff to call for help. An example was the 16-hour activation at Tustin Hospital in 2004. In another instance, the employee was only able to give us the name of the hospital before his cell phone's batteries failed. But that was enough to get our response going. Orange County has an inter-hospital radio/data system called HEAR/ReddiNet that any hospital can use to contact another hospital, which could in turn alert the hams using its Call-up List. The same relay alert can be done via the hospital's paramedic base radio, if one is present.

Pagers are also an important part of the HDSCS activation model. Even though each hospital has at least three member voice numbers to contact, day or night, it is possible that all might be busy or not answered by a person. This was the case when West Anaheim Medical Center lost phones on the morning of Field Day 2004, when most members were away from home. In a major mass casualty incident or potential evacuation situation, hospital staff may be unable to take the time to call numbers until an answer is received and then to give details to a member. For both of these circumstances, our hospitals have had one number to call, which brought a full response from HDSCS by setting off the pagers of all seven of the Coordinators.

For pager response, each hospital was assigned a unique three-digit code which the caller inputs instead of a return phone number. The three-digit number immediately identified the facility in trouble without the page recipients having to recognize the phone number or call it back. When a three-digit page was received, we attempted to contact the hospital for information on the emergency. If we got through, we got the details we need. If we can't get through, we went into a full response anyway.

An important ongoing task is to maintain all the hospitals' Call-up Lists. Members change work, home, cell and pager numbers often. These changes must be given to the affected hospitals immediately. The flip side of this is that our contacts at the hospitals undergo constant change, too. Leaders must keep checking to make sure that the appropriate contact person is aware of the Call-up List and where it is kept within the facility. When an updated list is sent by e-mail or FAX to any hospital, there should be follow-up to verify that it has gotten to key personnel in the facility, placed into the hospital's Emergency Procedures and Disaster Manual, and posted at for the PBX (switchboard) operators.

Activation plans would be worthless if the hospitals did not utilize them. In the chaos of a disaster, they must remember to call us and know how to do so. The NIMS-compliant Hospital Emergency Command System (HICS), used by all Orange County hospitals for mass-casualty incidents and other situations where an emergency is declared, calls for the Hospital Communications Officer to initiate an activation of Amateur Radio communications support. But a one-hospital switchboard or trunk line failure rarely results in a formal HICS activation.

To insure that hospitals practice contacting HDSCS, we includeD our activation in the mass-casualty drills that every hospital must perform over the course of a year. Rather than have hams in place within the hospital at the start of the drill, we pre-staged them nearby hospital must go through its call-up procedure before the hams entered and joined the net. Besides insuring that the hospitals are familiar with the location of their Call-up Lists and the need to use them, our members received the valuable experience of coming into the hospital and setting up as the simulated emergency unfolded.

Core Teams Provide Automatic Response

A tornado, earthquake, hurricane or other major disaster may disrupt all telephone communications over a wide area, making it impossible for hospitals to call for ham help. Hams cannot assume that city and county agencies will somehow know which hospitals are in need of help in such cases. No news is not necessarily good news and hospitals must not be afterthoughts in Amateur Radio disaster response.

Besides being on Call-up Lists, most HDSCS members have been Core Team Responders. This means that they have made a commitment that HDSCS is their primary Amateur Radio responsibility in a widespread disaster. They identified the hospital or hospitals closest to their home and work locations, and agreed to respond and check on the status of those facilities immediately upon learning of the disaster, without waiting for a call.

An earthquake, tornado or hurricane is its own alerting system. It shouldn't be necessary for hospitals to call when one of these occurs, and it isn't. Upon feeling the ground shake, HDSCS members automatically got on the air, began a net, and checked on their closest hospitals. Similarly, when HDSCS members learned of flooding or wildfires within or close to Orange County, the group activates a net and checks on the hospitals most likely to be affected.

Over the years, rapid automatic response has proved vital in several emergencies. After the twin Landers (magnitude 7.3) and Big Bear (magnitude 6.4) earthquakes that occurred during Field Day 1992, HDSCS members immediately left their homes and Field Day sites to check on every hospital in the county (34 at that time). We determined the status of most of them in less than 90 minutes and all of them within three hours. Member Gary Holoubek WB6GCT arrived at Buena Park Doctors Hospital to find it completely dark because the emergency generator had started and then failed. All of the facility's phones were down, too. Besides providing emergency communications, we obtained a priority response to the facility from Southern California Edison.

Immediate Core Team response was important during the Laguna firestorm of 1993. One hospital asked for support and told of difficulty contacting other hospitals in that part of our county. We immediately responded to that hospital and also to three others that were eventually affected, saving valuable time. Moments after the 2002 Placentia train collision took place, we were aware of the disaster and the location. We didn't wait for hospitals to call or page us, so when some of our hospitals called after getting their own Emergency Command Posts set up, our HDSCS communicators were already heading into these hospitals or getting parked, ready to go in.

In November 2008, when we heard reports that part of the Freeway Complex wildfire had jumped the 57 freeway and that Kindred Brea Hospital was in its path, HDSCS immediately established a net and sent four members toward that hospital, even though no request had yet been received. Getting there before traffic was too congested proved worthwhile when officials decided to evacuate the hospital about an hour after the first hams arrived.

Rounding Up the Hams

An up-to-date roster of trained and prepared responders is the most important tool for activation of members in a call-up response. Just jumping on a repeater and trying to get anyone you can, as April had to do in 1979, might bring some help. However, it carries the risk of attracting hams that are neither prepared nor suited for communications in a hospital environment. Hams on the HDSCS roster agreed to be hospital responders, to be ready and to participate in regular training and drills. Even if your community does not have a specialized hospital response group such as HDSCS, there should be a special list of hams identified for initial response to hospitals.

As with the hospital Call-up Lists, the rosters and First Wave lists must undergo constant review and revision. Members must take the mission seriously and promptly advise Coordinators of any changes in phone numbers and work schedules. Roster updates should be disseminated to all members.

In a Core Team response after an area-wide disaster, HDSCS members came up on our designated frequencies and advised Net Control to which hospitals they were responding, based on their proximity at the time. If Net Control determined that some hospitals are being "left out" while others are "overcovered," responders were immediately reassigned as needed. The primary goal in the initial response is to insure that all of our served hospitals are provided with a link to the outside world until their normal communications can be re-established.

Time to Act

Amateur Radio operators want our hobby to be known as a national resource. We like to wear T-shirts that say "Amateur Radio, When All Else Fails." But we are no resource at all if important local agencies such as hospitals don't know that we can help and don't know how they can access our services. We aren't a viable resource if we don't plan ahead for how we will activate rapidly and serve these agencies, keep the plans current, and back them up with practice and personal preparation.

Through regular contact with hospitals and with activation procedures in place, Amateur Radio will be of service to them long before all else fails. That's important, because when it comes to patients' lives and well-being, if hams wait until all else fails, they have waited too long.

Text and illustrations copyright © 2008 by Joseph D. and April A. Moell. All rights reserved.

Back to the HDSCS home page

This page updated 14 October 2018

It is far better to have a group of outside volunteer hams at the ready to go into the hospital and be specialists at performing communication tasks while the hospital folks go about their important patient care duties.

It is far better to have a group of outside volunteer hams at the ready to go into the hospital and be specialists at performing communication tasks while the hospital folks go about their important patient care duties.

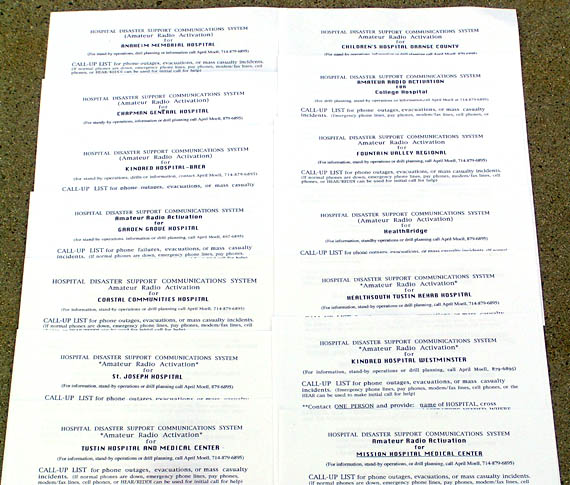

On display are Call-up Lists for 14 of the 33 facilities that were served by HDSCS. Each list was tailored for the facility's location and updated regularly. The list included both voice numbers and a unique pager code. HDSCS members were encouraged to monitor our repeaters whenever possible. A call there usually yielded some members who can respond immediately. But typically, more are needed and we turned to the roster. Besides a complete printout of members with home, work, cell and pager phone numbers for each, our Coordinators had special First Wave lists that identified the eight members who should be called first for each hospital, in daytime or evening. Because the hams on these lists were the ones likely to be closest and most available to the facility in need, our response time was greatly improved.

HDSCS members were encouraged to monitor our repeaters whenever possible. A call there usually yielded some members who can respond immediately. But typically, more are needed and we turned to the roster. Besides a complete printout of members with home, work, cell and pager phone numbers for each, our Coordinators had special First Wave lists that identified the eight members who should be called first for each hospital, in daytime or evening. Because the hams on these lists were the ones likely to be closest and most available to the facility in need, our response time was greatly improved.