When the Shaking Starts, It's Too Late to Plan

Personal Preparedness and the "Bug-Out Box" (Go-kit)

By Joe Moell KØOV

As published in the September 1999 issue of CQ-VHF Magazine

We have all seen stories about our fellow hams "saving the day" in a disaster or communications emergency. It's a good feeling to know that you're a ham and that you could do it too. Or could you?

If disaster struck you home town right now, would you know what to do? If an inattentive backhoe operator cut the telephone trunk lines to your local hospital, could you be of service? In either case, you won't be of much help from your home. You and other hams will have to go to the places where communications are needed. You will probably need to bring your own radio gear.

Is all the equipment that you would need ready to go right now? Are your batteries charged? Could you get on the air quickly and effectively from a disaster site or a damaged facility? What agencies and institutions will you be able to help? What will they expect of you? With whom will these agencies want to communicate? What radio paths will you use to contact or send messages to the people that they need to reach?

Simply put, if you haven't put some serious thought and effort into answering questions like this in advance, then you are not yet ready to be an emergency communicator. You might become one of the scores of hams who will get on the air to talk to each other about the disaster, but you won't provide any real support to the citizens of your community. You won't be a vital resource, you'll be a wasted resource.

Orange County's Plan Works

Since 1980, I have been privileged to be a member of Hospital Disaster Support Communication System (HDSCS), a special ARES group dedicated to the emergency communications needs of hospitals and health care facilities in Orange County, California. In that time, HDSCS has responded to over 100 actual communications failures. Some of them were the result of widespread disasters such as earthquakes, floods, and wildfires. The majority have been sudden telephone system outages due to computer crashes and construction accidents like the backhoe example above.

No matter what the cause, any interruption of normal communications at a hospital puts patient lives at risk. When there is not instant contact between internal units, or when staff members cannot rapidly reach outside doctors, blood banks, and suppliers, it's a disaster to them. In our area, hospitals know how to get hams to help in these situations "stat." Can they do so in your town?

Almost every time, our emergencies have begun with no advance warning. Nevertheless, our typical response time after an emergency alert is less than 30 minutes to the first ham's arrival at the hospital. It is not unusual to have a full contingent of a half dozen or more hams in place for department-to-department communications in 45 to 60 minutes.

Many of our hospitals have installed rooftop VHF multiband ham antennas and a very few have installed complete VHF-FM stations. But this pre-installed equipment is often not accessible, especially in the wee hours. HDSCS hams always bring their own gear to provide floor-to-floor communications. They usually use their own rigs for hospital-to-hospital and other external links, too. Typically, outside links are on the two-meter band. The 125 and 70 cm bands are used between units within a facility.

Many of our hospitals have installed rooftop VHF multiband ham antennas and a very few have installed complete VHF-FM stations. But this pre-installed equipment is often not accessible, especially in the wee hours. HDSCS hams always bring their own gear to provide floor-to-floor communications. They usually use their own rigs for hospital-to-hospital and other external links, too. Typically, outside links are on the two-meter band. The 125 and 70 cm bands are used between units within a facility.

To achieve rapid response time, our personal ham equipment must be organized and ready, 24 hours a day. In the early years, I kept a "bug-out bag" with me at all times, containing handi-talkies, batteries, cables, and small tools. This got me through a few activations, but it left a lot to be desired. The radios tended to bang around and get scuffed up in the floppy cloth bag. Cables got tangled and knotted. Telescoping whips got bent and broken. Usually everything was in there when I needed it, but if something wasn't, I couldn't tell it at a glance before heading out. I had to either dig around by hand or dump out all the contents to check.

Handi-talkies (HTs) are designed to hang on a belt or hold in front of your face, but not to stand on a table. HDSCS members learned early on not to wear HTs on belts when on a hospital unit, because the antenna's proximity to the body blocked incoming signals. Too many calls were being missed. When I stood my HTs on a table, they would fall over whenever I picked up my speaker-mike. I needed a better system.

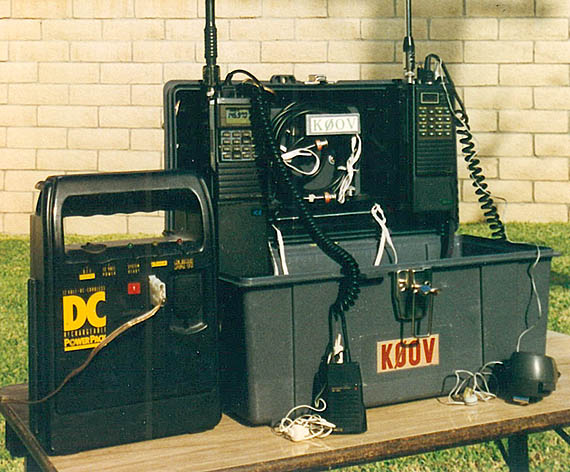

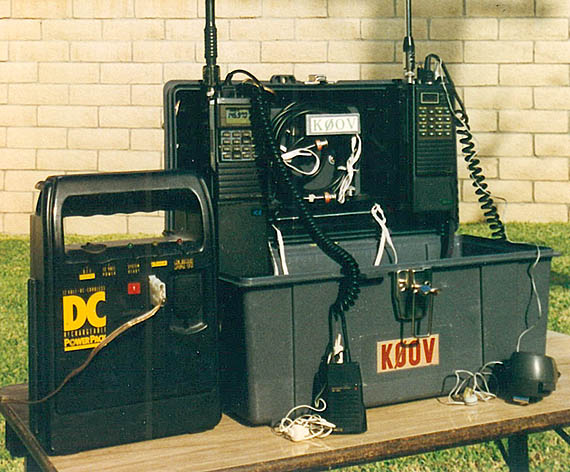

About this time, HDSCS member Jack Haddon WA6LWF (now a Silent Key) showed off his new equipment box with the lid modified to be a radio holder. I knew right away that his idea would be the basis of my readiness solution. A couple of weeks later I had finished a similar setup, with a few improvements.

The heavy plastic tool box cost only about eight dollars at a discount store. I cut up a coat hanger to make a rod that holds the lid vertical when operating, attached with captive bolts and wing nuts. The two radio holders bolted onto the lid are U-shaped pieces of steel from my junkbox. Hanging an HT's belt clip on one of these brackets keeps it firmly in an upright position against the lid. The whip antenna stays vertical and in the clear. I have two radio positions on the lid, one for the UHF internal net and one for the VHF external net. There's room in between to mount my scanner or another HT if needed.

An average HDSCS activation lasts three to four hours, but some have continued for 24 hours or more. Ordinary HT battery packs might not last through a long activation, so I wired the box with 13.8-volt connections to each radio location. The little 2-ampere 13.8 VDC supply that I carry along will keep the batteries charged when AC power is available. If it's not, my 7 ampere-hour sealed lead-acid battery pack will power everything.

My emergency kit also includes coax jumpers and adapters, so I can utilize any external antenna that may be available at a hospital. There's room in the box for 5/8-wavelength telescoping whips, a small bag of tools, flashlight, micro-cassette recorder. Cables and whips are secured to the lid with shoelaces. Velcro® strips could also be used. Either are much better than tape, which gets gummy, or wire ties, which break and get lost. It's easy to see at a glance that everything is in place and ready to go.

My emergency kit also includes coax jumpers and adapters, so I can utilize any external antenna that may be available at a hospital. There's room in the box for 5/8-wavelength telescoping whips, a small bag of tools, flashlight, micro-cassette recorder. Cables and whips are secured to the lid with shoelaces. Velcro® strips could also be used. Either are much better than tape, which gets gummy, or wire ties, which break and get lost. It's easy to see at a glance that everything is in place and ready to go.

Along with the box, I keep a notebook with HDSCS rosters, hospital directions, frequencies of other local ARES/RACES groups, message forms and so forth. A label on the box reminds me to take the notebook into the hospital with me. I keep additional equipment supplies in the vehicle, including more portable antennas, RF power amplifiers, rolls of coax, large power supply, AC distribution, triplexer, SWR meters, and so forth.

My "bug-out box" has stayed close to me for fifteen years and has served me well. From the Emergency Department of a major hospital, I placed autopatch calls to patients' families and to private physicians during a five-hour phone system failure. From the Command Post of another hospital, I directed a network of hams in several units while communicating with our countywide net on another band.

Those are just two examples; the box has been used many other times. In between emergencies and drills, it is ideal for fast station setup at public service event locations, such as parade announce stands and marathon mileposts. Most of the other HDSCS members now have their own quick-setup kits, using a variety of soft and hard enclosures in accordance with their personal preferences.

Plan For Yourself, Too

Plan For Yourself, Too

A "bug-out box" will keep you on the air during a communications emergency, but it's not the total solution for personal preparedness. What if a widespread disaster leaves you stranded, away from home? You'll need enough provisions to keep you functional, lest you become part of the problem instead of part of the solution.

Many ARES and RACES groups provide training in personal preparedness, with lists of suggestions for items that the comfort kit in your vehicle should include. I collected lists from the Web and several sources, then used them to create my personalized list, which includes my medications, first aid supplies, gloves, dust mask, hard hat, change of clothes, spare glasses, and much more. All of that stays in a big tub that I keep in my vehicle at all times. Make your own list, tailored to your own circumstances, and be sure that the most important items are always close by.

But that's still not the end of good personal preparedness. HDSCS's ability to respond to hospitals within minutes requires us to secure our homes quickly. Imagine that you are at home and a disaster has just struck. What steps would you take before departing to serve an agency? In what order?

Below is a sample Personal Preparedness Plan. This example assumes a damaging earthquake, because that's the most likely major disaster here in southern California. With a little modification, it would serve for a tornado or hurricane emergency. The idea is to attend to your personal post-disaster situation with the right priorities, without forgetting anything important. Give some thought to your own circumstances and create your own list.

Preplanning your reaction to a sudden disaster not only adds to your efficiency and makes you a faster responder to the agencies that depend on you, it also helps reduce your level of stress. Instead of flailing around and wondering what to do next, you'll be taking positive steps to control the situation.

Are you really ready? Remember, when the disaster strikes, it's too late to start planning.

Text and illustrations copyright © 1999 and 2015 by Joseph D. Moell. All rights reserved.

Back to the HDSCS home page

This page updated 12 January 2015

Many of our hospitals have installed rooftop VHF multiband ham antennas and a very few have installed complete VHF-FM stations. But this pre-installed equipment is often not accessible, especially in the wee hours. HDSCS hams always bring their own gear to provide floor-to-floor communications. They usually use their own rigs for hospital-to-hospital and other external links, too. Typically, outside links are on the two-meter band. The 125 and 70 cm bands are used between units within a facility.

Many of our hospitals have installed rooftop VHF multiband ham antennas and a very few have installed complete VHF-FM stations. But this pre-installed equipment is often not accessible, especially in the wee hours. HDSCS hams always bring their own gear to provide floor-to-floor communications. They usually use their own rigs for hospital-to-hospital and other external links, too. Typically, outside links are on the two-meter band. The 125 and 70 cm bands are used between units within a facility.

My emergency kit also includes coax jumpers and adapters, so I can utilize any external antenna that may be available at a hospital. There's room in the box for 5/8-wavelength telescoping whips, a small bag of tools, flashlight, micro-cassette recorder. Cables and whips are secured to the lid with shoelaces. Velcro® strips could also be used. Either are much better than tape, which gets gummy, or wire ties, which break and get lost. It's easy to see at a glance that everything is in place and ready to go.

My emergency kit also includes coax jumpers and adapters, so I can utilize any external antenna that may be available at a hospital. There's room in the box for 5/8-wavelength telescoping whips, a small bag of tools, flashlight, micro-cassette recorder. Cables and whips are secured to the lid with shoelaces. Velcro® strips could also be used. Either are much better than tape, which gets gummy, or wire ties, which break and get lost. It's easy to see at a glance that everything is in place and ready to go.

Plan For Yourself, Too

Plan For Yourself, Too